Beauty Is All Around: Theodore Richardson’s Paintings of Wrangell

Before there was Bob Ross, Theodore Richardson made his name as a prolific painter of Alaskan landscapes. Over decades, Richardson made frequent visits to Wrangell where he captured these scenes of extraordinary beauty.

Drawing Life

Theodore J. Richardson was born in Maine in 1855 and grew up in Minnesota, where he became a drawing instructor in 1880. In 1884, Richardson took a trip that would change his life forever, when he boarded the steamship Ancon for Alaska. As the January 5, 1916 Winona Daily News later described it:

“After his first visit to Alaska that field was his dream of interpretation, to be realized in a quarter of a century of devoted study of its varying shades of air and mist, snow and ice, rock and water... Alaska lifted him from black and white to watercolor.”

Richardson found fame and success as a painter of Alaskan scenes. For much of the world, Alaska was a mystery. Photographs could freeze moments in time, but Richardson’s paintbrush to convey Alaska’s bold, picturesque landscapes in vivid color. The January 30, 1891 Los Angeles Daily Herald wrote:

“His reproduction of the beautiful mountains, which in most cases are abrupt and striking, taken under many different circumstances of fog, evening haze and twilight, morning light, etc. are the admiration and delight of the beholder… Then there are the Indian huts and villages, the totem poles of the chiefs, and many surroundings of that far away land which are faithfully pictured in a masterly way.”

Richardson traveled throughout Alaska, but Wrangell was one of his first, and most visited, destinations to paint. As Wrangell evolved, Richardson was there to capture the changes and the timeless beauty.

Shutack Point

This painting depicts the homes and graves on Shustack Point, the peninsula which sticks out in front of Wrangell creating Etolin Harbor. In 1924, construction began on the Etolin Harbor Breakwater which would change the appearance of the point forever. (image credit: Theodore Richardson, Untitled, Coastal village, 1914. Anchorage Museum Collection, Gift of Len and Jo Braarud, 1989.014.011).

While Richardson’s signature may not be visible on this painting, the colors, style, and near-identical match with illustration from Our New Alaska (below) suggest it is an original Richardson painting. (image credit: Michael & Carolyn Nore Collection)

Chief’s House and Totem-Poles at Wrangell. This black-and-white drawing of Shustack’s Point looks southwest. The chief mentioned in the caption is Shustack, head of the Taal’kweidí, for whom the tip of the peninsula is named. Richardson included illustrations of carved Tlingit figures and a wooden spoon to the edge of this illustration. (image credit: Our New Alaska by Charles Hallock, 1886)

Indian Houses at Wrangell. Black-and-white illustration of Tlingit homes on Shustack Point, with Woronkofski Island in the background. (image credit: Our New Alaska by Charles Hallock, 1886. Free to use, public domain.)

Wolf Grave

Indian Grave Wolf Totem over Medicine Man Grave. This watercolor painting depicts a Tlingit-style log grave with a carved wolf on top. In the 1890s, the wolf carving was moved in front of the home of Kadashan, where it was frequently photographed at the base of the Kadashan poles. (image credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Free to use, public domain)

Indian Grave. This black-and-white illustration depicts the wolf carving atop the grave. It formerly sat next to the Killer Whale Grave Totem. (image credit: Our New Alaska by Charles Hallock, 1886. Free to use, public domain.)

Stikine River

Use the left-right arrows on the gallery above to see three paintings of the mouth of the Stikine River by Richardson.

Entrance to the Stickeen River. A black-and-white illustration of islands parting to reveal the mouth of the Stikine River, with mountains in the distance. This image was selected to appear before the title page of Our New Alaska. (image credit: Our New Alaska by Charles Hallock, 1886. Free to use, public domain.)

This version of the “Mouth of the Stickeen” painting hangs in the lobby of Wrangell’s James & Elsie Nolan Center. Unlike the other versions of this painting shown here, this one is in landscape orientation, and Richardson did not paint the furthest mountain peaks in the distance. (image credit: Alice Rooney)

Zimovia Strait

Theodore J. Richardson Sketching in Wrangell, Alaska. This iconic photograph is one of the most frequently featured images of Richardson. Many articles mention Richardson’s “floating studio” where he set up his easel to paint. This photograph was taken right off the shore of Wrangell, with Elephant’s Nose clearly visible to the left in the distance. (image credit: Hennepin County Library, donated by Myra L. Sutherland).

This painting of Elephant’s Nose may show the exact scene being painted by Richardson in the photograph above. Michael McCormack suggested that his grandfather, P.C. McCormack, may have commissioned this painting from Richardson since it shows the view from the former McCormack family home. (image credit: Michael McCormack)

Use the left and right arrows on the gallery above to view similar pieces to the Elephant’s Nose painting. Given the style, color, and perspective, these paintings may have been created around the same time.

Jack Mantle’s Boat. According to the 1900 Census of Wrangell, John “Jack” Mantle was a married, 43 year-old Canadian-born fisherman living in Wrangell. (image credit: Minneapolis Institute of Art. Free to use, public domain.)

Wrangell Beach. This painting was likely made north of Wrangell’s Petroglyph Beach, looking west. (image credit: Theodore Richardson, Beach, Wrangell, c. 1900. Anchorage Museum Collection, Gift of Len and Jo Braarud, 1989.014.005).

A small sailboat set against a sunset of purple, orange, and blue. (image credit: March in Montana 2025 Session I)

Shakes Island

This painting depicts Shakes Island inside Etolin Harbor at low tide, as well as other structures on the island which likely served as homes for the Naan.yaa.aayí clan. To the right, buildings on the peninsula may have been homes of the Tee-hit-tan clan. (image credit: March in Montana 2025 Session I)

Chief’s House. Richardson painted the two totems in front of the Shakes Island clan house: Gonakadet (left) and Bear Up The Mountain (right). While many photographers captured images of this home and its totems, this is one of the few images to depict the scene in full color. (image credit: Minneapolis Institute of Art. Free to use, public domain)

Raven Pole

Raven Totem Pole. The Raven Pole, carved by William Ukas in 1896, stands in front of a home on the hill. Richardson took liberties with landscape in the background, often making it appear larger and closer than it might in real life. Today, a version of this pole stands in Totem Park, and a smaller version carved by William Ukas’ son, Thomas, stands in front of the U.S. Post Office. (image credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Free to use, public domain)

Old Joe’s Boat

Old Joe’s Boat. It’s not clear who Joe was, but his canoe is likely draped in wet blankets in order to protect the wood from splitting. Shustack Point is visible in the background to the left. (image credit: 2010 Coeur d’Alene Art Auction, Lot 151)

While this painting does not feature Richardson’s signature, its resemblance to the other canoe painting signed by Richardson suggests this is in fact an original Richardson. (image credit: Michael and Carolyn Nore Collection)

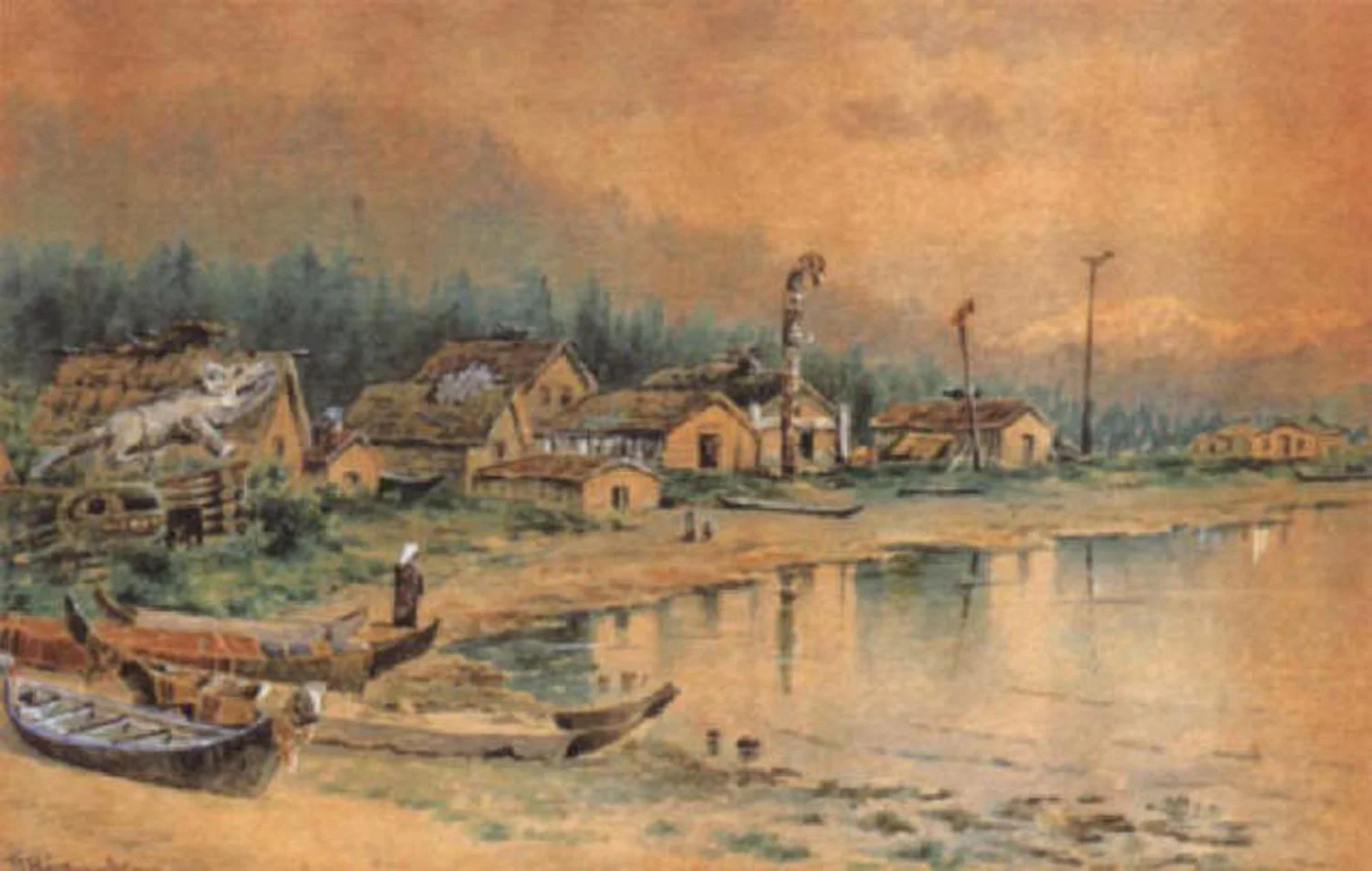

View of Wrangell

While this series of paintings is often identified as “View of Wrangell,” it is perhaps more appropriately identified as “View of Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw.” These paintings were made near the north end of the Tlingit village, close to modern-day Totem Park. To the left, the Wolf Grave Totem (mentioned earlier) is visible next to the Killer Whale Grave Totem. This row of houses led to Shakes Island. It is not clear how many versions of this painting Richardson made. Given that Richardson visited Wrangell many times, it may be a painting that Richardson composed every time he visited Wrangell, in effect, creating a time-lapse. (Read more in the Wrangell Sentinel: Life in Wrangell captured in 139-year-old watercolor painting)

Maybe Richardson

While this painting of Kadashan’s House lacks Theodore Richardson’s signature, it has the hallmarks of a Theodore Richardson painting. The colors, style, and time period depicted correspond to Richardson. (image credit: Michael & Carolyn Nore Collection)

Maybe Wrangell

Theodore Richardson was a prolific painter of Alaska, so much so that many of his pieces of art have made it online without any indication of where the paintings were made. Here are some paintings that look like they could be Wrangell, or they could possibly be some other place in Alaska.

Native Interior. A Tlingit woman draped in a robe sits inside a home surrounded by pots and other materials. A hole in the ceiling is designed to allow smoke to escape. (image credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Public domain, free to use.)

Use the left and right arrows on the image gallery above to switch between three different paintings by Theodore Richardson of Indigenous homes in Alaska.

Artistic Legacy

Theodore J. Richardson’s Sitka Studio. This photograph from the 1910s shows the walls of Richardson’s studio covered with his artwork, including pieces from Wrangell shown here. (image credit: Hennepin County Library Digital Collections)

In 1909, Theodore Richardson’s artwork received the Grand Prize at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. He told The Minneapolis Journal that Alaska was “the scenic wonderland of the world.” He was a recognized figure in Wrangell, where he stayed at the Wrangell Hotel. On December 21, 1914, the Juneau Empire wrote:

“For twenty-five years Richardson has been making the Alaskan trip once a year, and is known to a large circle of friends here. Three years ago Richardson spent the summer in Sitka and Juneau, but for the last two years made his summer headquarters at Wrangell. He formerly made the trip during the summer cruises of the steamer Spokane, and on each voyage would lecture of Alaska’s scenery, which he pronounced the greatest in the world.”

Theodore J. Richardson died November 19, 1914 at the age of 59.