The Eyes of Skak-Ish-Tin

Skak-Ish-Tin lived to be well over 100 years old. Although much of her life remains a mystery, the stories and images that survive offer glimpses into her extraordinary life.

Skak-Ish-Tin (left) photographed with her husband, Aaron Kohwow (right) inside their home by A.C. Pillsbury in 1898. The caption reads, “Blind Aaron and Squaw at Home, Wrangel, Alaska.” (Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons)

A World of Changes

It was the morning of New Years Day in 1907. Many in Wrangell awoke from the previous night’s revelry to learn that the town had lost a legend. The January 3, 1907 Alaska Sentinel wrote:

“The old native woman, who for years has been an object of great curiosity to Wrangell visitors, was found dead in her house near the electric light station, Tuesday morning. It was simply a death from old age and exposure, and therefore no inquest was held. The deceased was reputed to be over 116 years of age, and for many years has lived in the old shack where she died, with no other floor than the ground. She did her cooking over a fire built on the floor, the smoke escaping through a hole in the roof. A tin can full of money was found in the house.”

Skak-Ish-Tin lived alone in a Tlingit-style longhouse along the waterfront. Before her husband, Aaron Kohwow, died around 1899, he had been an early member of the Fort Wrangel Presbyterian mission and had served as an informal Indian policeman. Shortly before his death, he organized with fellow Tlingit fishermen to write a letter protesting the Alaska Packers Association for stealing ancestral salmon streams.

If Skak-Ish-Tin was indeed over 116 years old when she died, then she was older than George Vancouver’s 1893 voyage through southeast Alaska. She would have witnessed the Russians in the 1830s, the British Hudson Bay Company in the 1840s, the Stikine Gold Rush of 1861, the arrival of the United States and the Bombardment of Wrangell at the end of the 1860s, the Cassiar Gold Rush of the 1870s, and the other countless changes to the traditional Tlingit way of life.

In the foreground, a black-and-white photograph shows the home of Skak-Ish-Tin (right) with the Flying Raven pole in front. A figure is visible in front of the door, which may be Skak-Ish-Tin. In the background, a Google Street View image of Wrangell from 2022 shows the approximate area the old photograph was taken.

From her home along the waterfront, Skak-Ish-Tin could watch the world changing around her. Modern-style architecture replaced traditional longhouses. A long, wooden boardwalk connected homes and business along the waterfront all the way to Shakes Island. In 1905, Wrangell’s first electrical power plant opened next door to her home, bringing light to the darkness. The boundary between the gold-rush town of Fort Wrangel and the traditional Tlingit village of Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw was blurring.

By the end of the nineteenth century, one change meant a new life for Skak-Ish-Tin and many Tlingit in Wrangell: tourism.

Photos of Skak-Ish-Tin

Skak-Ish-Tin’s home was perfectly situated to encounter the many tourists who visited Wrangell aboard steamships from the south. Her home sat along the walking route to Shakes Island, a key landmark for visitors who wanted to see totem poles and the inside of Tlingit homes. Much of Alaska was still a mystery to the outside world, and curiosity among the public was high. Some of the visitors to Alaska brought cameras capable of capturing images which could be sold for newspapers, magazines, and postcards.

What follows is a collection of photographs which may feature Skak-Ish-Tin. Most of these photos do not feature a description or identify the people inside the photographs. Skak-Ish-Tin is identified by visual recognition alone, which is not always perfect.

1892, S.R. Stoddard. Three women sit on the floor of a smokey longhouse around a cauldron. A man in a suit is partially visible off the right-han edge of the photograph. Skak-Ish-Tin may be the woman sitting in the middle. (Photo credit: Private Collection)

1892, S.R. Stoddard. A woman who may be Skak-Ish-Tin is seen sitting on the floor as light from a fire illuminates her face. (Photo credit: Private Collection)

1895, Winter & Pond. Two elderly women (Skak-Ish-Tin on the right) and a cat inside the doorway of what may be Skak-Ish-Tin’s home. The caption reads, “Old Tlingit Women, Fort Wrangel, Alaska. Copyright 1895 by Winter & Pond.” (Photo credit: New York Public Library)

1895, Winter & Pond. Another photograph of the two women and the cat inside the doorway. The caption reads, “Old Thlingit Women, Alaska. Copyright by Winter and Pond.” (Photo credit: Alaska State Library)

Undated, Photographer Unknown. Three elderly Tlingit women sitting in front of a longhouse. Skak-Ish-Tin sits to the right with her head wrapped in a scarf. A man in a vest stands to the left, with the prow of a canoe visible behind him. (Photo credit: Michael and Carolyn Nore Collection)

1898, A.C. Pillsbury. A portrait of Skak-Ish-Tin from inside her home. The caption reads, “Blind Aaron’s wife.”(Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons)

1898, A.C. Pillsbury. A portrait of Skak-Ish-Tin outside of her home. (Photo credit: State Archives in Stavanger)

1898, A.C. Pillsbury. Skak-Ish-Tin in front of her home with an elderly man and woman on each side. (Photo credit: State Archives in Stavanger)

Undated, John Elmer Worden. J.E. Worden arrived in Fort Wrangel in 1898. The caption reads, “‘Skak-Ish-Tin,’ Native, over 100 years old, Wrangell, Alaska, Photo by Worden.” This photo is also available from the American Museum of Natural History and the Alaska State Library (version 1 | version 2). (Photo credit: Wellcome Collection)

Undated, Photographer Unknown. Skak-Ish-Tin sitting in front of her home with a cane by her side. The figure of a man standing in a suit is partially visible off the left edge of the photograph. (Photo credit: Michael and Carolyn Nore Collection)

1904, F.H. Howell. Skak-Ish-Tin sitting in the doorway of her home. Her hair appears more gray than the other photos. The caption reads, “Skak-Ish-Stin 108 Years Old, Copyright by F.H. Lowell, 1904.” (Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons)

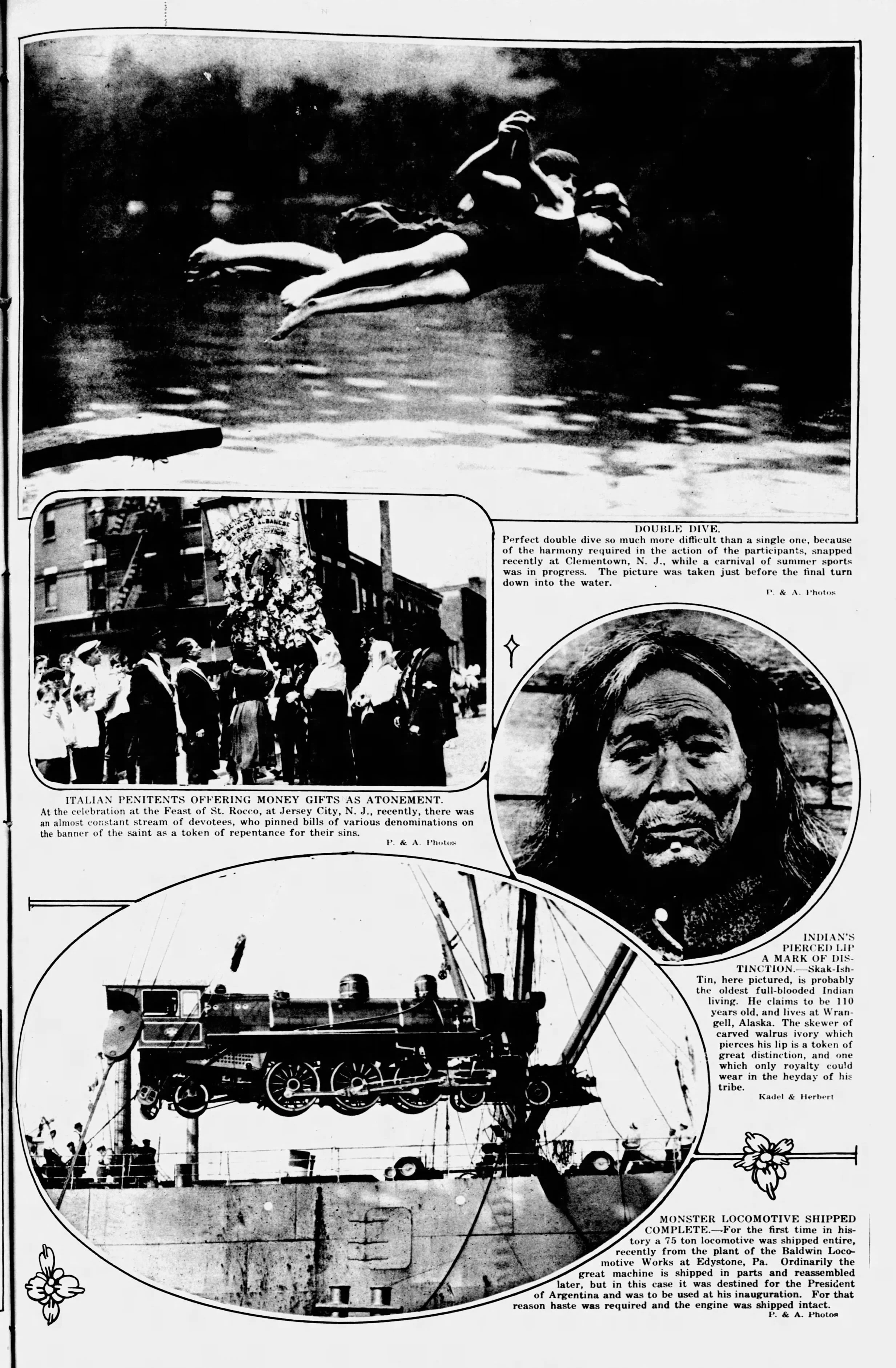

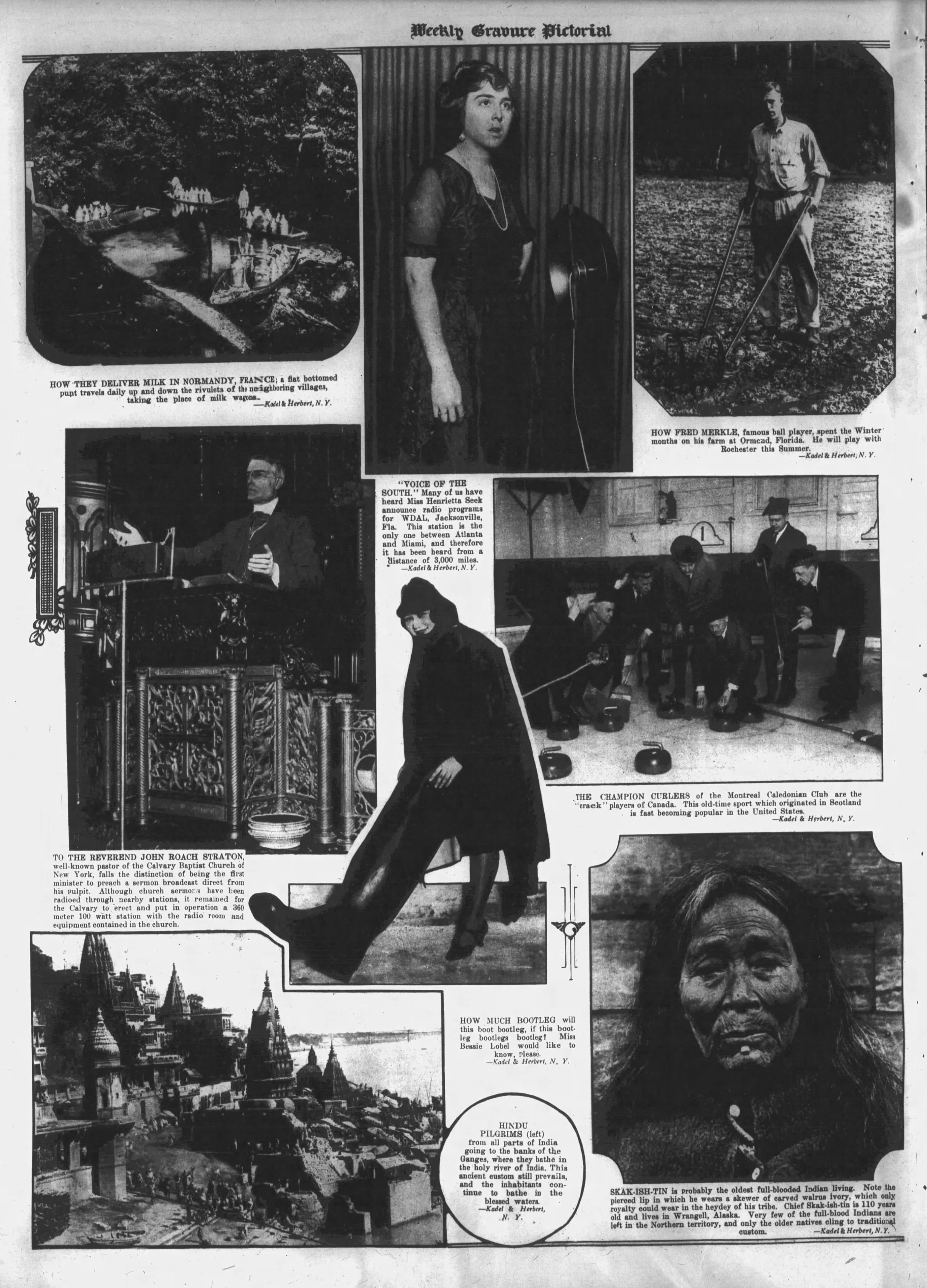

A page from the Piqua Leader Dispatch of January 7, 1916. The headline reads, “Alaska’s Peculiar Indians” and features a photo in the center of a Tlingit woman with the caption, “Aged Indian Woman Wearing ‘Labret’ Lip Ornament.” The article features the passage, “The labret or lip ornament is fast disappearing, but there is one woman in Wrangle who still wears it. She appears to be about ninety years of age, although the tourist is told she is one hundred and ten. This hideous face decoration is peculiar to the Alaska Indians.”

The Lip Labret

One feature of Skak-Ish-Tin’s appearance that captured the attention of visitors was her lip piercing called a labret. Labrets are found in many cultures, but in traditional Tlingit culture, women wore labrets in their lower lip as a sign of status. According to Xh’unei, Lance A. Twitchell, the Tlingit word for labret is xh’eint’áax’aa while Richard Daunehauer’s Tlingit Spelling Book identifies the word for a small labret as k’anoox.

For tourists from the south who were unfamiliar with such practices, lip piercings were both shocking and captivating. As one tourist who visited Wrangell wrote in the May 2, 1896 Scranton Tribune:

“On our return trip and at another place we visited, we spoke with an old woman, who was sick and likely to die. She was evidently very old, but it was impossible to determine her age, so wrinkled and smoke dried was she; indeed, she resembled a mummy rather than a human being. Her skin was the hue of tobacco and her natural ugliness was intensified by a labret. This labret consists of a piece of polished bone about an inch and a half long and over a half inch in width thrust through the lower lip, making it impossible to keep the mouth closed and leaving the toothless gums fully exposed. It is, however, regarded as a mark of respectability. Her ruling passion for business was displayed by offering to sell me her labret for ‘two dollar’ and an idol, three feet high, for ‘five dollar.’ ”

Another tourist wrote in the October 15, 1898 Elmira Star Gazette:

“At Fort Wrangle I saw an old Tlingit woman sitting upon her doorstep. I walked up to her to ask some question, and, quite incidentally, of course, to get a peep into her house. She took the bone which protrudes from her chin and offered to sell it to me for a quarter, or, as the Alaska Indians say, for ‘two bits.’ ”

Both examples may have been Skak-Ish-Tin, as evidence by this passage from Sourdough, Lucy Ware, an unpublished semi-autobiographical memoir by Lynn Worden Holmes, daughter of Wrangell photographer John E. Worden:

“Skak-Ish-Tin wore a mother-hubbard wrapper under her cape-like blanket. She had her real ivory labret in her lower lip, so Lucy guessed the tourists hadn’t been around lately. Old Skak always wore bone ones then and would obligingly take out the ornament and sell it. Her precious ivory one she saved for days when no boats called.”

An illustration of lip labrets by George Thornton Emmons from his book, The Tlingit Indians.

Today, the Burke Museum possesses a bone labret acquired by George Thornton Emmons in Wrangell, and the Smithsonian possesses a quartz crystal labret also acquired by Emmons in Wrangell. The practice of lip piercing labrets has diminished in modern times. According to the Icy Strait Point Tour Guide Manual from 2018, “Ornamentation traditionally included some hair dressing, ear and nose piercing, labrets, bracelets, face painting, and tattooing. Most of these facets of adornment are practiced today, excluding the labret.”

Photographic Legacy

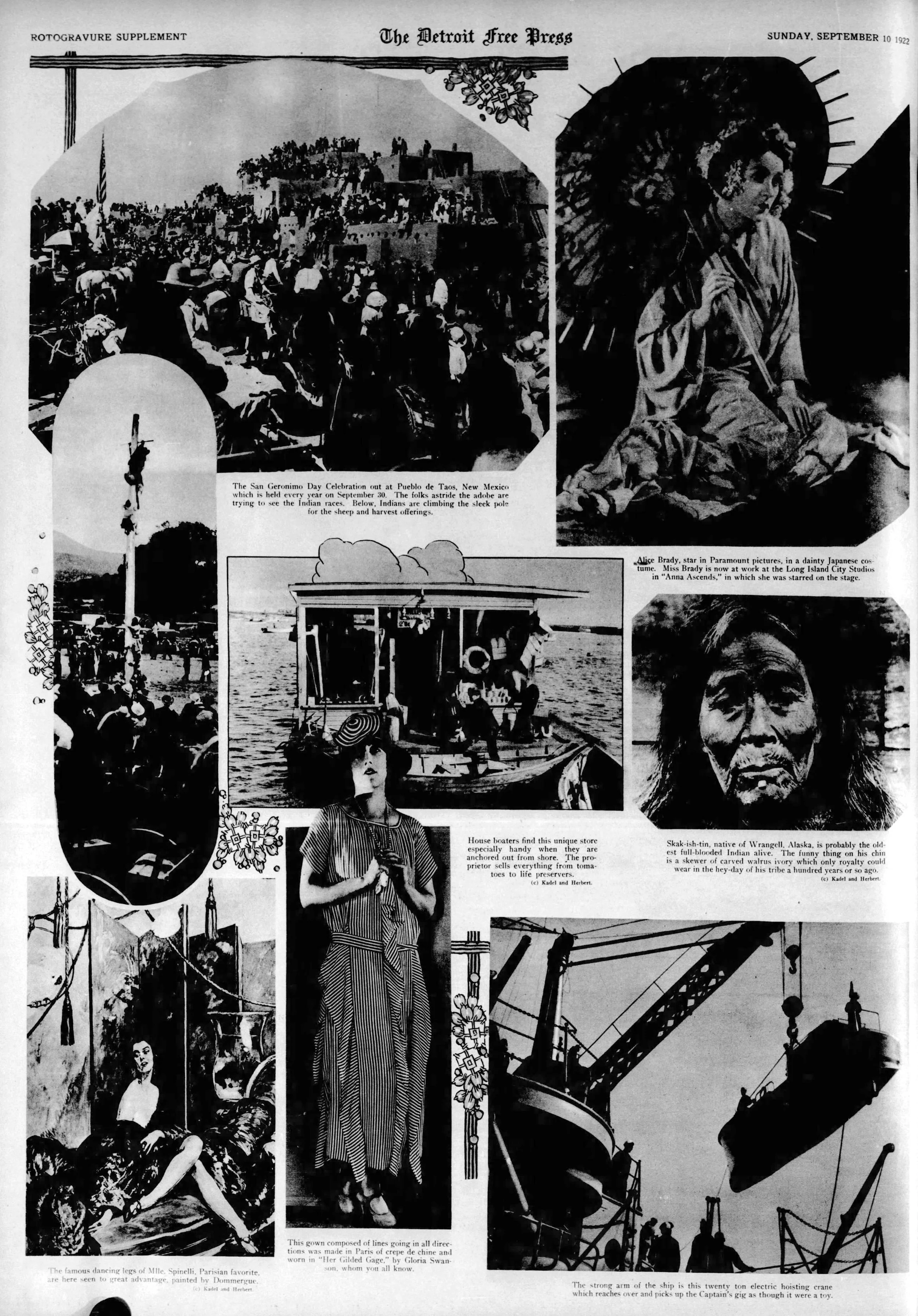

Of all the photographs taken of Skak-Ish-Tin, the most widely circulated has been the photograph taken by J.E. Worden. It is a striking portrait of Skak-Ish-Tin up close, looking directly into the camera, with her gray hair and wrinkles in clear detail. In the early 1920s, the photograph found circulation among many newspapers:

These newspapers incorrectly identified Skak-Ish-Tin as a man and commented on the labret, as well. For example, the Detroit Free Press of September 10, 1922 wrote:

“Skak-ish-tin, native of Wrangell, Alaska, is probably the oldest full-blooded Indian alive. The funny thing on his chin is a skewer of carved walrus ivory which only royalty could wear in the hey-day of his tribe a hundred years or so ago.”

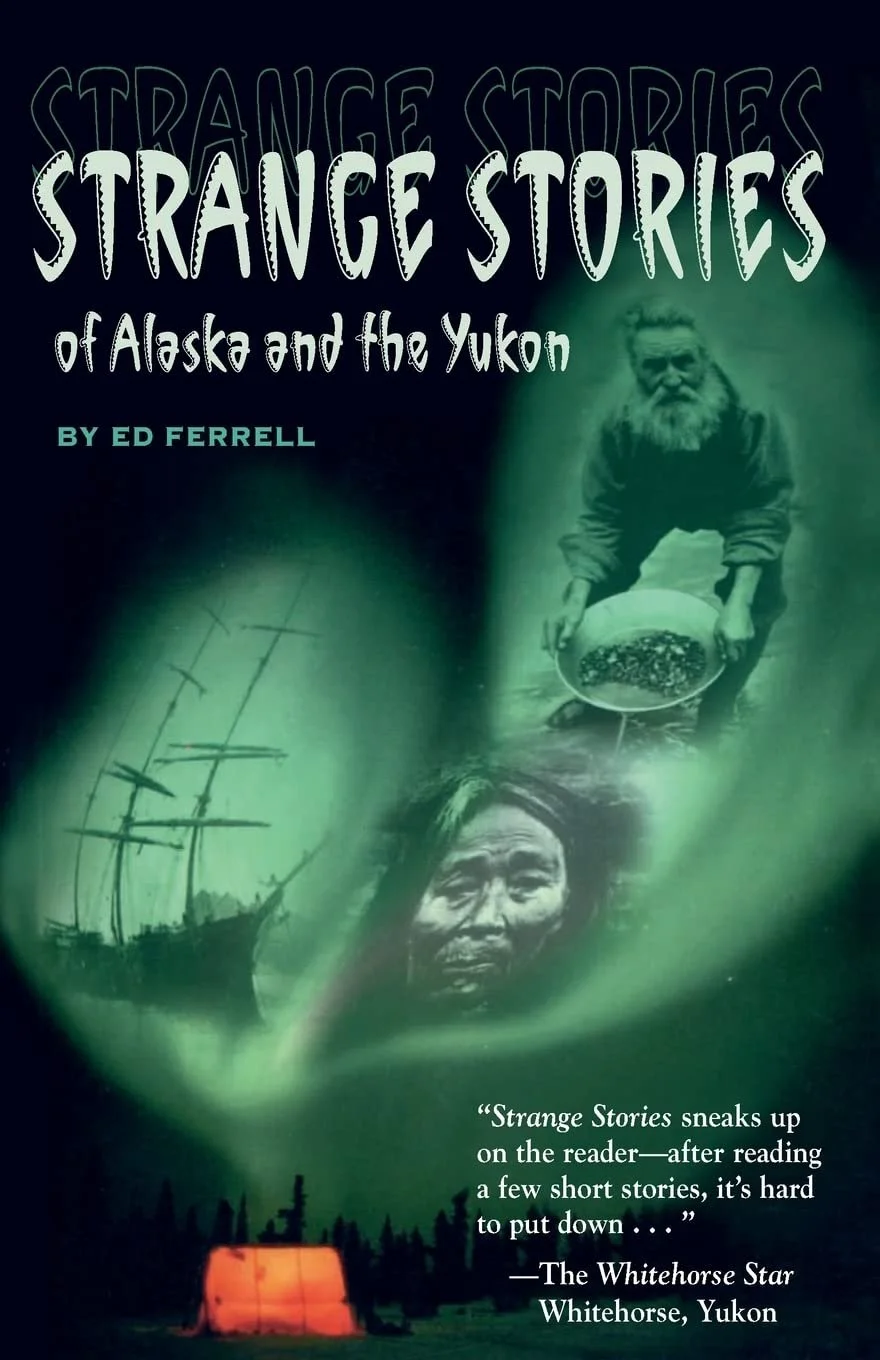

In 1996, Skak-Ish-Tin’s face appeared as a ghostly image on the cover of the book Strange Stories of Alaska and the Yukon by Ed Ferrell.

Skak-Ish-Tin’s photograph by Worden remains a popular image today on Facebook where it is frequently shared and reposted. A copy of the photograph posted in May 2022 in the Facebook group Native North American Indian - Old Photos has over 10,000 likes and has been shared over one-thousand times. Many of the comments posted by users are highly complimentary, reflecting on Skak-Ish-Tin’s beauty, poise, and wisdom. It is a clear departure from the caustic comments of the past.

But many commentators also suggest that Skak-Ish-Tin appears sad, even heartbroken, in Worden’s phtograph. Having lived such a long life, Skak-Ish-Tin certainly experienced loss and grief, and that may be reflected in her face. But old cameras of her era required subjects to remain perfectly motionless while the lens was open, which led many people to appear somber and unsmiling. One passage from Lynn Worden Holmes’ memoir suggest that Skak-Ish-Tin was not without joy. In this scene, the author visits Skak-Ish-Tin in her home and describes a shared moment between the young girl and the elderly woman:

“Lucy hadn’t much time to stay but she wanted to see Skak wash her hands so she made signs toward the box where the soapberries were. Skak obligingly took the berries out of the box and squeezed them in her hands. She rubbed them hard and the berries frothed like soap. Then Lucy ran to the water barrel and brought a dipper full of water and the old woman rinsed her hands and dried them on a gunny sack. She laughed then, laughed until her brown face was fuller than ever of crinkly seams. Her black eyes were tightly closed while the ivory button in her lower lip jerked up and down.”