Killer Whale Grave Totem

🪵 Part of a Series on Wrangell Totems 🪵

Rising from the shoreline of Wrangell, the Killer Whale Grave Totem stands as a memorial and a masterpiece. A favorite of photographers, painters, and visitors to Wrangell’s Tlingit village, the Killer Whale Grave Totem became the centerpiece of Fort Wrangel’s public square.

Graves of KaachXana.áakʼw

The first written description of the Killer Whale Grave Totem may be from Eliza Scidmore, who visited Fort Wrangel in 1883 and later wrote:

“Over the graves of the dead, which are square log boxes or houses, they put full-length representations of the dead man’s totemic beast, or smooth poles finished at the top with the family crest. One old chief’s tomb at Fort Wrangel has a very realistic whale on its moss-grown roof, another a bear, and another an otter.”

It’s not clear when the Killer Whale Grave Totem began. During the ceremony for the U.S. Army’s apology for the 1869 Bombardment of Wrangell, Tlingit historian and carver Mike Aak’wtaatseen Hoyt suggested the carving may have been dedicated to Shx’ átoo:

“Is one that I believe was carved perhaps for Shx’ átoo himself, after the bombardment. It first shows up in paintings and photographs in the 1880s, so a little after the bombardment itself. It is on a grave marker... Using sort of that plus a little bit of, maybe you can call it inference or deduction, it is possible or perhaps even likely that this was carved as a grave marker for Shx’ átoo. It matches the time frame as well as the locations that were prominent.”

One of the next earliest written mentions of the Killer Whale Grave Totem came in November 1887, when photographer William H. Partridge ran an advertisement for his extensive catalogue of “Alaska views,” including fifteen images from Fort Wrangel. Among the list was “7876 - Indian graves, Fort Wrangel—the whale and the wolf” followed by “7760 - Ditto.” (image source: DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

This photograph, “7760” by Partridge shows that both totem carvings are still complete with all pieces attached, but the wood shows areas where paint has worn away. A thin layer of moss covers most of the Wolf Grave Totem, while the Killer Whale Grave Totem shows much less moss. (image source: Presbyterian Historical Society)

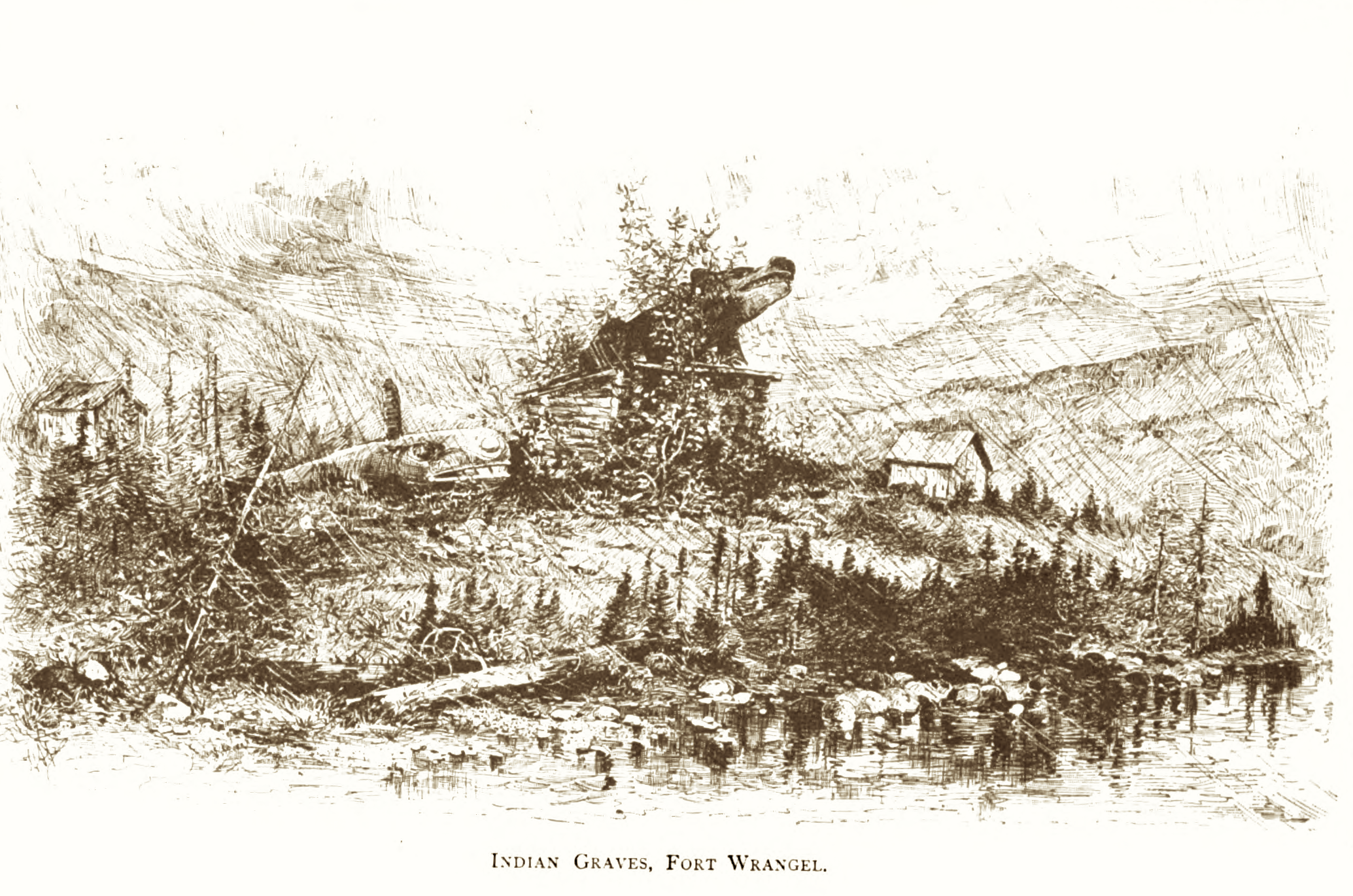

This illustration from John Muir’s Picturesque Alaska (published 1888) is an example of one of many pieces of artwork depicting these carvings. The scene’s unique perspective is from over the water, showing the carvings rising up above the coastline below. According to the book, “At Fort Wrangell the tourist finds the largest assemblage of totem poles and two remarkable graves, one surmounted by a rudely carved whale, and the other by a huge figure of a wolf. The totem poles serves as emblems of the clans or family divisions of the various tribes.”

A group of men (circa 1889) stand in front of the grave totems, while one man places his hand on the mouth of the Killer Whale Grave Totem. Throughout their existence, people would approach, touch, and be photographed with these carvings. The inscription on the photograph reads, “Indian Town, Fort Wrangle, Alaska. Peterson Bro’s Photo’s, Juneau, Alaska.” (image source: British Columbia Archives)

One of the last recorded accounts of the Killer Whale Grave Totem in its original location appeared in the March 23, 1890 edition of the San Francisco Chronicle:

“There are two remarkable graves to be seen here. A little log hut is constructed and in this was deposited the dead body of the chief, or his ashes if the body had been cremated. On the top is a figure of an animal carved in wood. One of these graves has a wolf above and the other a whale, but the latter is so much overgrown with rank brush that only the whale’s teeth and head show out from the surrounding vegetation…”

Determining the Original Location

This is one of the last known photographs of these two grave totems together. In the background, a new building appears that was not present in earlier photographs. We can use this building to pinpoint the historic location of these two carvings. (image source: Wikipedia Commons)

For countless visitors disembarking from steamships at the north end of the harbor, the Killer Whale Grave Totem and its neighboring Wolf Grave Totem were their first close-up introduction to Tlingit carvings. The carvings proved popular with tourists who frequently photographed, painted, and posed with it.

Using this historic photograph, we can estimate the distance from the Kiks.ádi Totem Pole to the house that was built behind the Killer Whale and Wolf Grave Totems. Using the height of the Kiks.ádi pole (32 feet) as a measuring tool, we can estimate that the house stood roughly 256 feet from the Kiks.ádi pole.

Using this 1914 map (foreground) of Wrangell by the Sanborn Fire Company, wen can identify that the building constructed behind the Killer Whale and Wolf Grave Totems was this (circled in red). By superimposing the 1914 map over a modern-day satellite image, we can see that the building used to stand in the southern half of the Sentry Hardware & Marine parking lot.

Fort Wrangel Courtyard

(image source: Wikipedia Commons)

Around 1890, the Killer Whale Grave Totem (without its dorsal fin) was moved to the center of Fort Wrangel’s public square. This location was deeply culturally and socially significant for the town of Fort Wrangel. The courtyard square was a common gathering place, featured a flagpole with the American flag, and was positioned in front of one of Alaska’s only federal courthouses.

It’s not clear who moved the Killer Whale Grave Totem or their intentions. It began as a grave marker, but when it moved into Fort Wrangel, it left behind the burial house. Deprived of its original context, the carving became a piece of art in the public square. Unlike a tall totem pole featuring multiple symbols and stories, the Killer Whale Grave Totem was conceptually simpler for outsiders to grasp. Fort Wrangel’s embrace of this piece of art suggests the fledgling community’s recognition of the legacy and contributions of its Tlingit neighbors.

The Klondike Gold Rush (1898-1902) brought thousands of gold-miners through Fort Wrangel on their way to the Klondike. In order to ensure order during the mayhem, the U.S. Army stationed soldiers inside the garrison of Fort Wrangel for the third and final time in history. According to The Sketch magazine of February 8, 1899, the Killer Whale Grave Totem was “used by United States soldiers as a ‘clothes-horse,’” suggesting they hung their clothing across the carving to dry.

August 14, 1904. John N. Cobb. (image source: University of Washington)

In 1908, William Fletcher King visited Fort Wrangel. In his book, Reminiscences, he remarked, “Near Fort Wrangel we saw the celebrated whale-totem so commonly seen in photographs.”

A photograph of the Killer Whale Grave Totem inside the Fort Wrangel courtyard by photographer John E. Thwaites, circa 1913. (credit: University of Washington)

Photographer John E. Thwaites stands with his hand on the Killer Whale Grave Totem, circa 1913.

The last-known photograph of the Killer Whale Grave Totem inside the Fort Wrangel courtyard may be from this photograph taken January 1, 1914 featuring Wrangell’s townspeople gathered on the hill rising up to the Fort Wrangel buildings. In the distance to the right, behind a man wearing a black suit and hat, is the Killer Whale Grave Totem. (credit: Michael and Carolyn Nore Collection)

Post Office Lawn

(credit: Alice Rooney)

In July 2025, Wrangell celebrated the raising of five new totem carvings, including a detailed replica of the Killer Whale Grave Totem in front of the U.S. Post office — a historical parallel to the location of the same carving over 100 years before.